Below the Salt

Valerija Intihar

Back to the salt mines

A thick layer underfoot—coarse, industrial, used to blunt the freeze. Ground zero is laid in salt, the purpose not being purity or preservation, but something closer to abrasion. Surface crunches while moving through space, preserving not safety, but rather a surface memory.

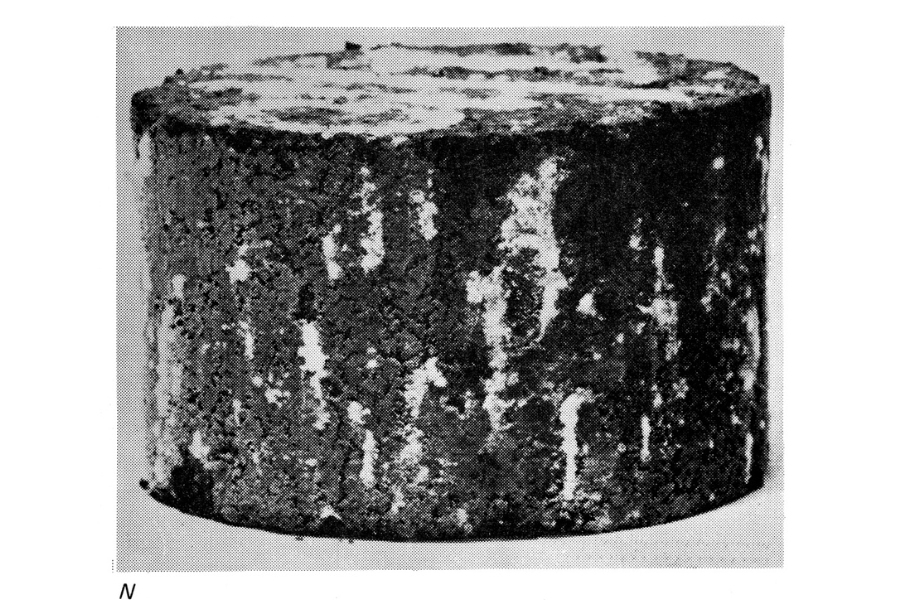

Scattered fragments emerge in the crystalline: cores and spines of asphalt samples, cast-off, retrieved from the shallow guts of roads and under-bridges. A number of knee pads rest among them—originally produced in foam, now cast in solid aluminium, burnished by sand, not wear; with cold and weighty structures. No body fills them, yet the pressure is implied—they hold a posture that remains bent and still: to kneel here is to endure. The artist makes a shift—material found scattered is carefully picked, stored, archived, and then loops back to be (purposefully) grounded. From use to monument, from function to fossil.

The remains, both mundane and specific, suggest a kind of sacred waste—a term previously addressed in Gerkman’s exhibition Sacred Waste Lot at DobraVaga (2023)—referring to matter displaced from the cycles of utility but not discarded. As in the logic of memorials and ruins, where objects of labor or trauma become sites of reverence, some infrastructural relics resist disappearance. They stay as offerings, too exhausted to function, yet too charged to throw away. Although the artist’s processes are embedded in systematizing, he now does not catalogue the artefacts but lets them rest, half-submerged—inviting something closer to ritual than reason.

In the early years of Slovenia’s independence, highways became the surface of sovereignty, and workers—many holdovers from Yugoslav brigades or redirected from socialist infrastructure projects—found themselves building the outlines of a new state. Infrastructure projects accelerated under slogans like “Building a Future,” serving as both literal and symbolic acts of nation-building. The artist’s collection of hundreds of asphalt cores transforms these utilitarian remnants into markers of that broader vision—built by hand, knee, and sweat. As Slovenia emerged from the Yugoslav federation in the 1990s, new construction visibly expressed independence, shaping both territory and national imagination. Amid the shift from collective Yugoslav ideals to a neoliberal framework, labor became more precarious and its traces increasingly aestheticized. The ambient space the artist constructs evokes the ghosts of a certain era’s ambition, condensed in polished protection and overlit surfaces.

Often relying on remnants of the former Yugoslav construction apparatus, state-owned enterprises were restructured or privatized, and labor conditions shifted: permanent contracts gave way to temporary work, standardized protections were unevenly enforced, and safety equipment lagged behind industry standards. While the roads promised future connectivity, workers often faced fractured realities—precarious contracts, skimpy gear, irregular wages, and long hours under slogans framing their efforts as national pride. The collective ethos of “Brotherhood and Unity” gave way to personal hustle and silent compliance. Gravel, asphalt, and the improvised conditions—where bodies absorb the cost of transition—form part of the material and historical field that Gerkman continues to research.

As in Marita Sturken’s idea of sacred waste, some materials become untouchable not because of their sacredness, but because of the discomfort they carry: a history of labor that does not fit neatly into progress narratives. They resist recycling or repair. Their placement doesn’t try to clean or explain the artefacts, but lets them sit heavy with what they were produced for, and of the people who used them.

Glow thickens. A grid-like structure mounted on the wall, each element turned sharply downward, hums and hovers—street lamps no longer guiding, rather glaring and insisting on the surface. The orange sodium light presses onto the grain and into itself, folding vision into repetition, into rhythm that can be observed from the window during a highway car ride. Bearing the precise, cold, indifferent semblance of the industrial, the sculpture casts the viewer not as witness but as surveillance—there is no above here; the light does not reach outward, only returns to itself or its twin. A system illuminates itself endlessly in a state where visibility equals value, and darkness implies delay or failure. The lamps once lit up the construction of new nations and the new economies, but they also illuminate nothing now—besides each other and the empty salt below, in a feedback loop of symbolic progress, often disconnected from the material exhaustion it required.The descent continues throughout the space, gliding deeper, reaching the underground. The viewer’s gaze is paralleled by the soft, steady one of a robot camera navigating the infrastructural underworld, the digestive system of the city, composed of pipes, concrete and flooded passages. Their veins run largely unseen and uninterrupted below the visible conduits of movement and memory, and the automated camera there being neither the explorer nor intruder. Its fully mechanized gaze marks a shift from embodied observation to automated monitoring: the eye becomes disembodied, efficient, released from exhaustion or perspective. In this de-subjectivized view, the figure of the worker disappears, replaced by a seamless optic that registers everything and understands nothing.

What persists in the gallery space is not ruin, but residue—of automated labor, of materials outliving their purpose, of the rather recent future building. Gerkman’s work is in this residue, his practice moving between fieldwork and archive, between the cast-off and the reassembled—materials not used, but rather returned to visibility. In his spatial installations, he compresses time; moments of progress, transition, erosion and waiting. Built in salt—and below it—is a momentary pause in the circulation of things. A granular void to feel the weight of the surface.

We would like to thank the company Bom Trade from Novi Sad for the salt donation.

Photos by: Lin Gerkman