Touch at First Glance

As our interaction with the world becomes increasingly condensed and reduced in the flatness of the handheld screen, Touch at First Glance seeks to elicit a heightened sense of touch and bodily engagement in an exhibition environment. The installation seen, or rather experienced here, is the first iteration of Žarko Aleksić and Sini Rinne-Kanto’s 2022 research project on sensory integration rooms with the overarching shared interest in touch and its role in present-day society. From the importance of touch for mammals on their way to becoming fully sentient beings and in their ability to develop structural and functional changes in the brain – also known as neuroplasticity – to the technological revolution and the question of surveillance (unlike vision and hearing, in the realm of touch one cannot surveil as one cannot touch without being touched) and domination of the other, the issues surrounding touch are many and complex. Indeed, a more nuanced understanding of the role of the senses is required as we relentlessly navigate the world of sensory overload and unfocused gaze, which has led to detachment and alienation from the world and other beings, exacerbated by the recent COVID-19 pandemic and the sheer reduction in the amount of physical touch.

Sensory integration rooms were first developed in the 1960s as a therapy for children to develop the senses, improve cognitive and emotional abilities, and help people to better understand and process sensory stimuli. The rooms were designed as specially equipped material environments with an installation focusing on light, sound and objects to touch. The positive benefits of these environments are numerous, ranging from helping people to better control their sensory experiences to reducing stress, anxiety and hypersensitivity to certain stimuli. Using this historical framework as a loose starting point, the exhibition explores the latent potential of these spaces and the redistribution of the sensory. The exhibition inquires into the perceptually dominant conditions that allow some subjectivities to be visible and audible, asking what is worthy of our attention and what role the senses play in this multi-sensory understanding of the world.

The epistemology of the senses has been much debated in the philosophical and phenomenological tradition. During the Renaissance, the five senses were understood to form a hierarchical system from the highest sense of sight down to touch. The concept of the self, the ego and the eye as the centre of the world was confirmed in the 15th century with the formal introduction of perspective into the academic tradition. Today, vision and hearing are considered to be the privileged social senses. In contrast, the other three are considered archaic sensory remnants with a purely private function, usually suppressed by the code of culture, as Juhani Pallasmaa describes in The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses.1

More recently, however, a ‘sensory turn’ has swept the academy, inspiring artists to explore the aesthetic potential of the non-visual senses. The role of touch in art spaces has also grown significantly as more and more studies point to the social, cognitive and even therapeutic value of handling objects. Mike Kelley’s Test Room Containing Multiple Stimuli Known to Elicit Curiosity and Manipulatory Responses and A Dance Incorporating Movements Derived from Experiments by Harry F. Harlow and Choreographed in the Manner of Martha Graham (1999), as its title suggests, explores the role of control, education and manipulation in human behaviour. In this work, the stage is dominated by playroom objects, referring to the American psychologist Harry Harlow and his study of the affective behaviour of primates and evoking the architecture and ambience considered typical of sensory integration rooms.

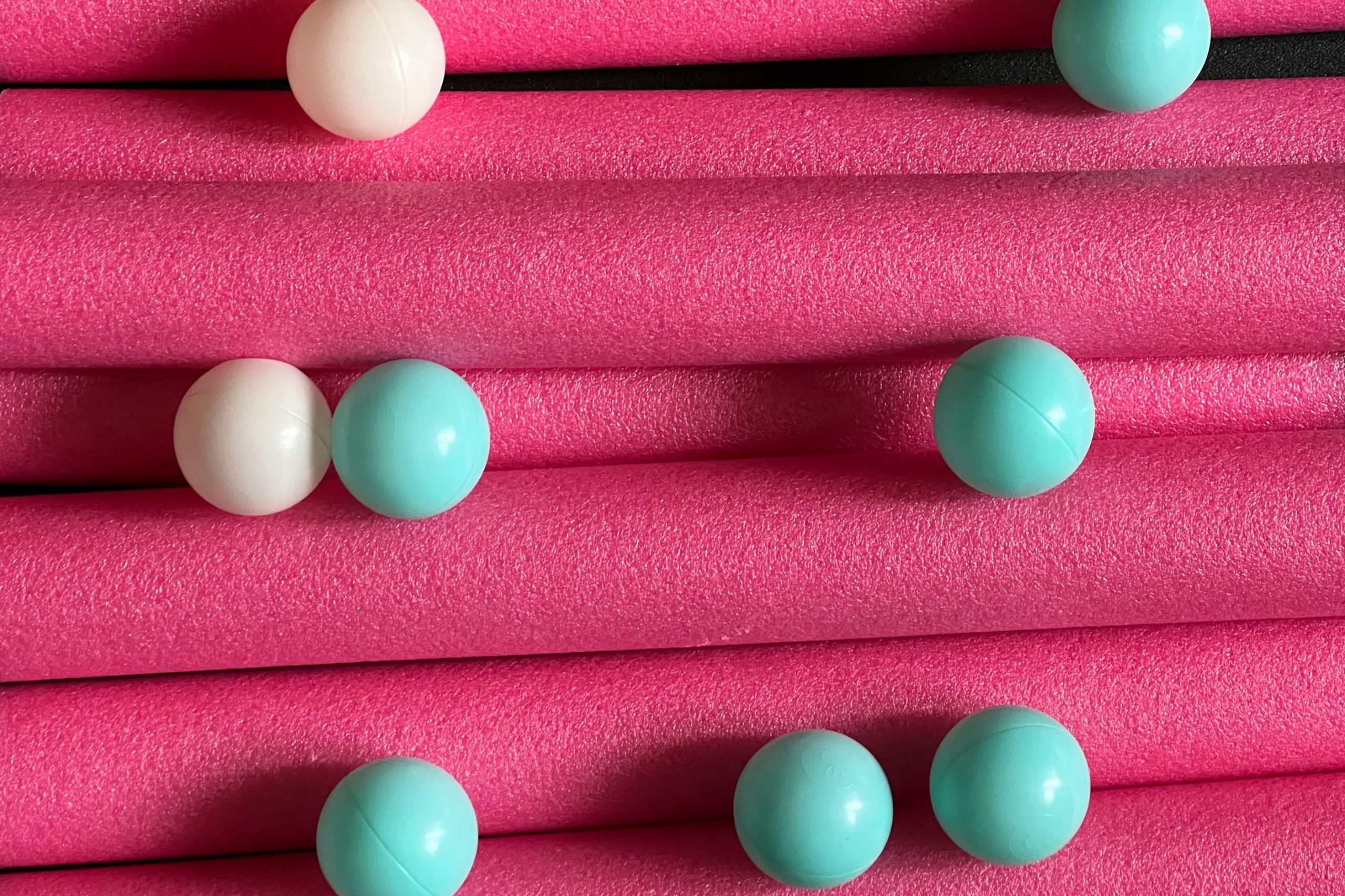

In Touch at First Sight, the installation is a loose simulation of a sensory integration room, with specific objects designed based on research that addresses tactile deprivation and the numbness it causes. Bright colours, playfulness, and shapes invite visitors to experience sensory stimuli in various ways to tactile participation through movable, loose parts in the gallery space. Here, walls and objects in space are not only external, material stimuli that invade our peripersonal space, but also powerful visual cues to orient our bodies. The exhibition actively seeks to disrupt the established institutional hierarchy of the senses by relying on multiple multi-sensory learning strategies. It aims to engage three senses – tactile, vestibular and proprioceptive – and their interaction. Proprioception is the bodily sensation that transmits information from our body to our brain and results from specialised sensory receptors in our muscles and tendons. However, proprioception cannot tell the brain the overall orientation of the body in relation to gravity (upright, horizontal, tilted). For this, we rely on another sense of the body called vestibular, which, like hearing, relies on specialised receptors outside our inner ear.

The exhibition is supported by Culture Moves Europe, The Finnish Embassy in Belgrade, the University of Vienna and the Austrian Cultural Forum Belgrade.

1Juhani Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses, (John Wiley & Sons Inc, 1996)

Photos: N. Nikolić